For immediate attention contact, Email: summit@fortuneforum.org and , Tel: 00 44 (0) 207 791 1717

On 17 October people around the world have been invited to watch, screen and share a new documentary to mark the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. Disparity not only highlights failings in the foreign aid industry, but it also hopes to provide new solutions to tackle the ever-growing gulf between the rich and the poor. In an attempt to hold the largest screening event in history, the documentary will be launched and free to view on YouTube in six different languages during a 24-hour world premiere event across different time zones.

Both Disparity and the upcoming Real Aid Campaign are the brainchild of the Indian philanthropist and aid campaigner Renu Mehta, launched in collaboration with the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). All of it has one, basic aim: to eradicate global economic disparity. As Mehta puts it: “These are the millennia old stories of struggle against country and corporate greed that ravages more than half the world’s population”.

The film features interviews with leading economists, aid experts, industry insiders and Nobel Laureates such as Noam Chomsky, Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz, as well as narration from the actor Ben Kingsley, who is best known for playing the title role in the 1982 film Gandhi.

Mehta says it is the first documentary to explore the connections and collusion of aid structures and the vested interests of donor nations, examining how aid can be connected to military and geopolitics, often supporting a combination of business, political and trade interests in donor countries. While it is a major challenge to hold these governments to account, Mehta tells Equal Times: “I would like the Disparity film to act as a tool to raise awareness, not only for local disparities, but for global audiences to connect the dots.”

The Real Aid Campaign

Yet, Disparity and the Real Aid Campaign is not only about the failures of foreign aid; it also shares the often untold success stories in the fight against global poverty and provides insights into alternate ways that foreign and development aid could be structured.

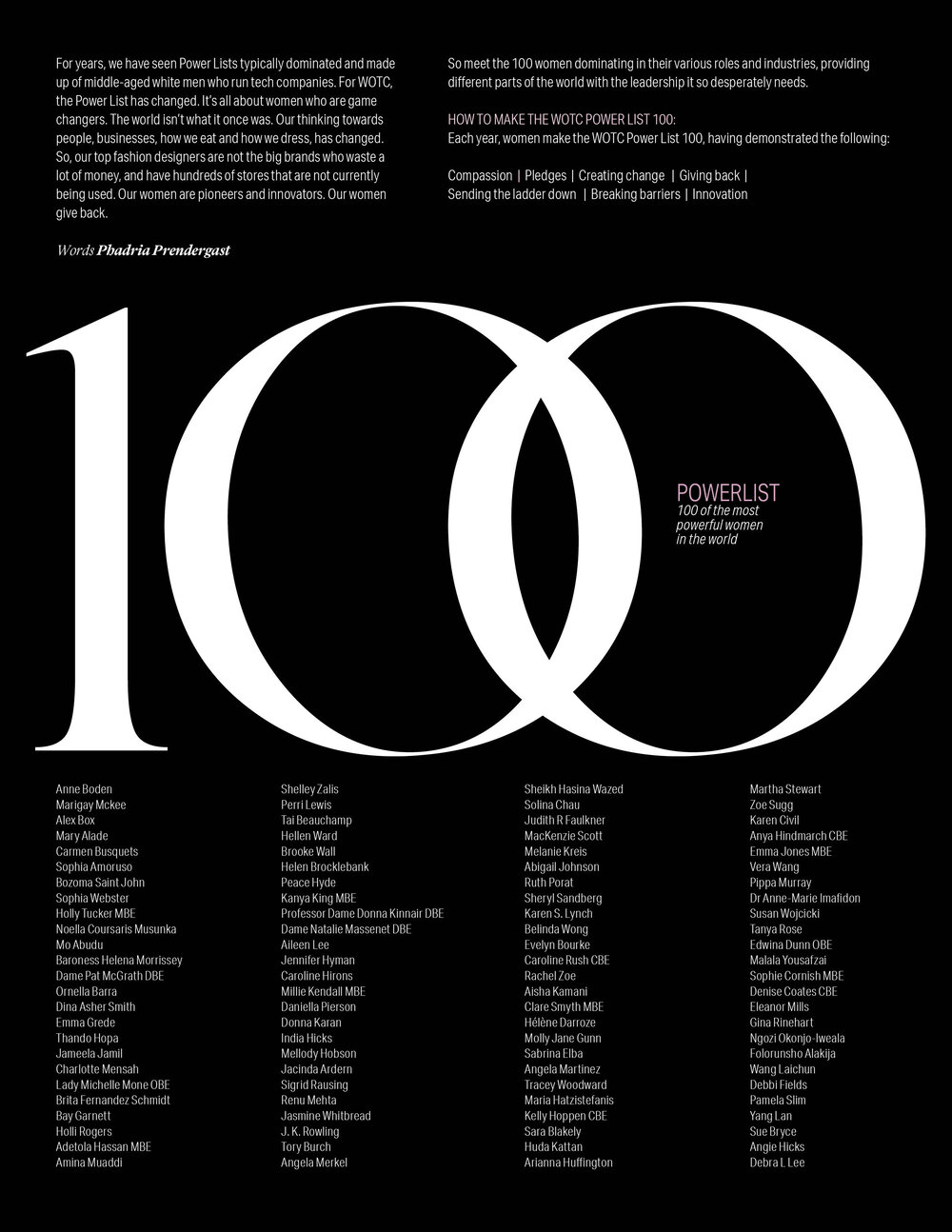

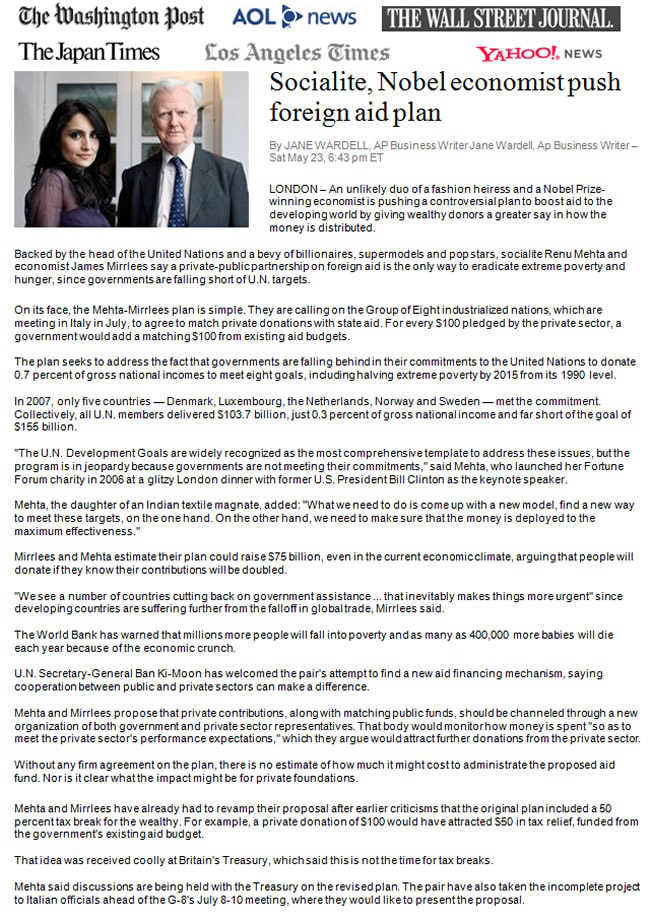

Co-chairing the Real Aid Campaign with Mehta is José Ramos-Horta, the former president of Timor-Leste and a joint winner of the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize. Together they will be launching initiatives on the 17th of each month, starting this October, to draw attention to the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which offers a roadmap of how to build a better world by 2030. Mehta has been involved with a variety of initiatives with the aim of eradicating poverty, including the development of the Mehta/Mirrlees (MM) Aid Model, co-authored with the late Scottish economist Sir James Mirrlees.

Launched in 2009 before the global call for tax justice really took off, the MM Aid Model is based on major policy changes to foreign aid donations and includes recommendations for businesses to contribute 1 per cent of profits, and those in developing countries to contribute 2 per cent, to poverty-alleviating initiatives in the Global South. Mehta believes that if the model – which is the driving force behind the Real Aid Campaign – is taken up globally, it could potentially raise US$100 billion per year towards increasing and improving the delivery of global development aid. “If major richer governments used 10 per cent of their aid budgets to match charity appeals it could positively impact over a billion lives,” says Mehta.

The UK Department for International Development (DfID) has adopted several aspects of the model, including utilising its aid budget to match private sector donations (UK Aid Match) and setting up an Independent Commission for Aid Impact, as well as a Global Innovation Fund, which offers grants, loans and investments for innovations aimed at improving the lives of those living under US$5 a day. According to Mehta, these initiatives have raised almost US$300m of additional funding.

When asked how her model fits in with global civil society’s call for tax justice and tax reforms as the key to economic justice over philanthropy, she responded: “I do not state that philanthropy is the best path to tackling inequality. Tax justice is essential to level the playing field and I wholeheartedly support it,” she says. “But it’s a not binary choice. There are a whole cluster of interventions that need to be deployed. I made Disparity because most people are oblivious to how government foreign aid, a US$150 billion industry, is spent and they have no say in it.”

Furthermore, Mehta says an important aspect of the fight for equality is solidarity with the international trade union movement, as workers around the world are on the frontline of this struggle. “From Australia to Africa to South America, large corporations mining precious natural resources subject workers to appalling conditions. From Sierra Leone to Congo to Liberia, civil wars over resources have led to deeper poverty. From India to Nigeria, children are subjected to child slavery. From Russia to Brazil, indigenous communities risk their lives to stop agrobusiness and mining companies. From the Philippines to Senegal to Peru, international companies are hauling in swathes of fish, emptying food supplies and depriving livelihoods for local fisherman,” she says. “These issues impact on the lives and the families of trade unionists across the world. Together we are stronger than working alone.”

But Mehta sees both Disparity and the Real Aid Campaign as having a purely enabling role. “We are not fundraising directly for charities, instead we are appealing to citizens to raise their voice, to help transform aid policies,” she explains. But in order to enable and inform, campaigners need data, and more importantly, the general public needs more stories highlighting the connection between aid, corporations and the ties to the geopolitical aims of donor nations. This is where the IFJ Development Aid Portal comes in.

A portal of accountability

What began as an interview with the Belgian journalist and former IFJ president Philippe Leruth for the film, later developed into the worldwide launch event spearheaded by the current IFJ deputy general secretary, Jeremy Dear.

“The big issue for us at the IFJ is around the reporting of development and on global poverty. We hope the film and campaign can be the kick-off point for better journalistic coverage,” explains Dear. “We believe that if you shine a light on the issues of aid and development you will find information that enables citizens to make better decisions about the delivery of aid or question how their taxpayer money is being spent.”

The IFJ Development Aid Portal will enable civil society organisations, frontline aid workers and community-based organisations within developing countries, to be able to upload stories, case studies, statistics and images that journalists can then search to get into direct contact with sources that are directly involved.

Dear refers to having a ‘twin track’ approach, as the IFJ is creating a platform to promote good practice, but also to expose bad practice and create more transparency.

“The idea is frontline organisations being able to provide information also covers people who want to shine a light on where development goes wrong, where money goes missing, where projects are useless, or where local communities are actually being discriminated against or excluded from the benefits of projects,” says Dear.

The platform is also about helping to keep those who live in local communities and expose malpractice a bit safer. “By having a platform to get to journalists in donor countries involved, there is better protection,” Dear explains. “For example, an environmental activist in the Amazon being able to get a story about a UK funded project that is leading to deforestation or pollution into the media in the UK or Europe, will have more impact there because it will raise questions about the way aid or development money is being used.”

In order to encourage good journalistic practices, only union journalists who have signed up to a code of conduct will be eligible to access the portal, including a commitment to ethical principles based on the IFJ’s Global Code of Ethical Journalism. Dear says; “I think we also have to make it clear to those uploading stories that they have to be certain that they want to link to journalists to get the story out, because we cannot make any guarantees that in the global media there are not journalists that may seek to exploit them. So, there is an education process, as well as vetting and standard-setting.”

‘The Donors’ Dilemma’ – From Charity to Social Justice

Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah – 24th February 2014

————————————————

This column by Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah is part of Global Policy’s e-book, ‘The Donors’ Dilemma: Emergence, Convergence and the Future of Aid’, edited by Andy Sumner. Contributions from academics and practitioners will be serialised on Global Policy until the e-book’s release in the first quarter of 2014.

This column by Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah is part of Global Policy’s e-book, ‘The Donors’ Dilemma: Emergence, Convergence and the Future of Aid’, edited by Andy Sumner. Contributions from academics and practitioners will be serialised on Global Policy until the e-book’s release in the first quarter of 2014.

There is no denying that foreign aid has been and will continue for some time to be an important source of finance of ending absolute poverty and promoting economic development. But the days of the Official Development Assistance (ODA) paradigm as we know it are numbered.

Aid is the manifestation of a peculiar historical context. We have built a world order in which there are unprecedented and unacceptable levels of socio-economic inequality. These extreme disparities have led to the creation of our current system of ODA, in which rich countries allocate a relatively small amount to alleviate the extreme manifestations of poverty around the world. We have developed guidelines, rules, norms and systems to regulate what counts and what doesn’t count as aid, all for very sensible reasons.

The reasons why aid is unlikely to survive much longer in its current form are well-rehearsed; five stand out. First, input-based measures have limited value. When David Cameron promised to address the problems caused by flooding in the UK in February 2013, he said “money is no object” in helping those affected by extreme weather; he didn’t say “we aim to set aside 0.x% of GNP to activities that we hope will help”. In almost every other area of public policy, we are seeing the emergence of results-based metrics, and there is no reason to think aid will escape. Secondly, the ‘us and them’ nature of ODA will continue to be under attack by public confidence in the aid in the rich world, especially as there will be new pressures to reduce government direct spending in. I accept that aid is a tiny fraction of public spending, but the current framework is easy to cast in zero sum terms. The emergence of novel match-funding schemes may be welcome innovations but they also signal a shift in the idea that there is a collective public commitment to ODA. Thirdly, there is the widely recorded relative decline in the importance of aid in the context of other flows that impact development, coupled (fourthly) with the fact that there are middle income countries who seem reluctant to participate in the ODA system. The current situation in which the ‘fight’ against poverty relies centrally on ODA and a specialist cadre of aid-workers seems antiquated, if not outright neo-colonial. Finally, even amongst established donors, there seem to be growing frustrations about an overly-restrictive ODA system that ties their hand (perhaps rightly) when it comes to allocating expenditure. For example, development in the Horn of Africa might best be helped through investments in security infrastructure not ODA-ble expenditure, and the climate-development nexus creates all sorts of new challenges about what should count as aid or not.

Of course, there are several short term process questions that will need to be addressed in the immediate future. There is an on-going need for aid to become more transparent, adaptable and smarter. ODA needs to be able to reach citizens in need and respond to their needs, as opposed to donor priorities taking precedence. Civil society actors need to be engaged in more meaningful ways, across the life-cycle of aid from design to delivery to monitoring.

However, in long-historical terms, I am convinced that the commitment by some rich countries to allocate 0.7% of GNP to alleviating poverty in the poorest parts of the world will be seen not as the high point of a global commitment to equality but instead as the low point of a system desperate to find policy bandaids to fix structural flaws.

However, my argument here is not some reactionary protest against the need for serious public investment to promote sustainable development but rather it is to point out that we need a radical transformation in the nature of aid and development cooperation to reflect emerging 21st century realities. It is a progressive’s plea that we need a new system, with additional resources, to tackle poverty and inequality.

By 2030, we need several fundamental shifts in the way the development sector works if we are to make a meaningful impact on poverty, inequality and sustainability. For a start, I hope we will have seen a shift to output measures, such as those likely to be embodied in the post-2015 sustainable development goals. For better or worse, the Millennium Development Goals ushered new focus in development finance. Now we need MDGs 2.0 that make ‘money is no object’ sort of commitments to addressing major sustainable development challenges, that obviously involve donor commitments but also involve a range of other actors, not least business, civil society organisations and developing country governments. Despite the limitations of a goal-based approach, it could nevertheless help shift the focus of development from inputs to outcomes, and broaden involvement beyond established donor governments.

By 2030, we need several fundamental shifts in the way the development sector works if we are to make a meaningful impact on poverty, inequality and sustainability. For a start, I hope we will have seen a shift to output measures, such as those likely to be embodied in the post-2015 sustainable development goals. For better or worse, the Millennium Development Goals ushered new focus in development finance. Now we need MDGs 2.0 that make ‘money is no object’ sort of commitments to addressing major sustainable development challenges, that obviously involve donor commitments but also involve a range of other actors, not least business, civil society organisations and developing country governments. Despite the limitations of a goal-based approach, it could nevertheless help shift the focus of development from inputs to outcomes, and broaden involvement beyond established donor governments.

I hope that in 2030 the core focus of the development community will be as much about inequality as it is about ending extreme poverty. Sadly it seems likely that even in the most optimistic scenario, there will still be large numbers of people living in extreme poverty, thus the focus on improving the lives of these people must be retained. However, as economic inequality risks spiralling out of control, both within countries and at a global level, an equally important focus of the development community should be on promoting equality. With the world’s richest 85 people already controlling more wealth than the poorest half of the world’s population, we may well be winning the ‘fight’ against poverty but we are losing the war against inequality.

This will require a fundamental shift from thinking of aid as charity from to the rich to the poor, to seeing these issues through a social justice lens. Nowhere is this need more evident, than with climate change. Protecting the world’s poor from the disastrous impacts of climate change – something that they had the least to do with – cannot be a question of what is a reasonable allocation of public funding to set aside, but one of doing what it takes to adapt and mitigate. If David Cameron thinks money is no object when it comes to flood victims in the UK, he and his fellow world leaders (including business leaders) have to think along the same lines for all people impacted by extreme weather.

This will require a fundamental shift from thinking of aid as charity from to the rich to the poor, to seeing these issues through a social justice lens. Nowhere is this need more evident, than with climate change. Protecting the world’s poor from the disastrous impacts of climate change – something that they had the least to do with – cannot be a question of what is a reasonable allocation of public funding to set aside, but one of doing what it takes to adapt and mitigate. If David Cameron thinks money is no object when it comes to flood victims in the UK, he and his fellow world leaders (including business leaders) have to think along the same lines for all people impacted by extreme weather.

Finally, I hope that by 2030, we won’t be talking about ‘donors’ anymore. I have been in countless conversations in recent years where the word ‘donors’ has been unhelpfully bandied around, used variously to mean things like ‘development cash-cows’, ‘knights to the rescue’, or ‘neo-imperialist forces’. Already, it is possible to see the limitations of this category. As new development actors emerge and new flows thicken, the term will become even more outdated. Perhaps the best indicator of a successful transformation in the development sector will be if the term ‘donor’ becomes as meaningless a grouping in international affairs in 2030 as say the ‘Communist bloc’ or ‘British Empire’ seem to today.

To get to anything like the scenario described here, we will need an equally radical transformation of the institutions and processes we have at our disposal. Today, we have a set of international economic institutions that were designed in the 1930s, that hardly reflect contemporary geopolitics and that are overly statist in their approach. These archaic institutions were created on an assumption of rich superiority and poor inferiority, and need urgent reform. Similarly, the rules governing ODA need to be overhauled or ditched altogether (though I see the risks of the latter). Initiatives like the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC), with its multi-stakeholder approach, signal a step in the right direction. But we need more radical change, more quickly.

Dr Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah is Secretary General of CIVICUS, the global civil society alliance. @civicussg

For further press coverage: http://fortuneforum.org/press.html